By Peter Lindblad

Instinct told him there was something special about this young bucking bronco.

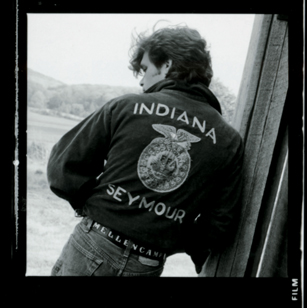

Privy to the 1976 sessions for John Mellencamp’s very first demos, Mike Wanchic was in awe of his untamed spirit and raw artistry. Just a kid from Seymour, Indiana, Mellencamp was no shrinking violet.

“Oh, he was a wild man! He was a wild man,” exclaimed Wanchic, the guitarist who’s been joined at the hip with Mellencamp full-time since 1978. “I was just looking at the other guy saying, ‘Who is this guy?’ He was like a sparkler going off – wild, with energy, and crazy ideas.”

To put it simply, Wanchic said, “I saw a star,” and he added, “I thought, this is where I should be hitching a wagon, which I’m doing 43 years later.”

Through thick and thin, Wanchic and Mellencamp have persevered, with Wanchic as his lieutenant. They’ve played together on 23 studio albums, going all the way back to the days when Mellencamp was marketed as Johnny Cougar, then John Cougar and then John Cougar Mellencamp. His glorious rock ‘n roll past will be mined thoroughly when Mellencamp plays Green Bay’s Weidner Center March 25 and Madison’s Overture Center for the Arts March 26.

Don’t expect Mellencamp and company to go too far off the beaten path with the set lists.

“Well, the way I would put this is, we’re trying to satisfy as many people (as possible) … because all our fans are true fans, we’ve got to touch on all bases,” said Wanchic. “There’s that musical history we have that’s really rich and tied to everybody’s lives, memories, jobs, sports, deaths – all that stuff. And it’s like that for me, too. Even as a fan of our own music, the first songs that I absolutely fought to play, we have to play, and we know that. And so, we do. We honor the crowd that way.”

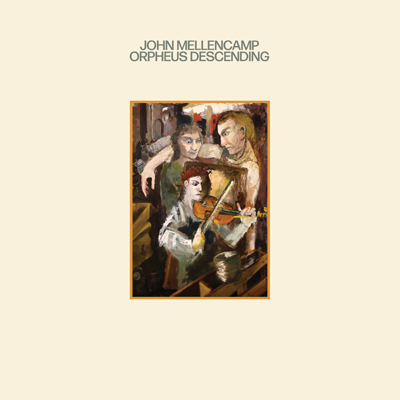

Not content to rest on his laurels, Mellencamp is still making new music, having released the deeply personal Orpheus Descending in 2023. As Wanchic notes, “We’re a viable musical entity. Records are still being made.”

Toned down to reflect a more meditative aesthetic, Orpheus Descending sees the master songwriter looking inward and aging like fine wine, accepting that his hitmaking days are behind him and making music that’s meaningful for him. And if others are moved, too, that’s icing on the cake.

“It’s such a personal record for John,” said Wanchic. “Those sort of records are made in privacy, in the quiet, and you put them out knowing that there’s only going to be a certain amount of people that are going to want to like grab onto it, and listen to it and understand it, because it’s not consumable by the mass public and that’s not the intention. That’s not the intention of any of the records in recent history. We’ve done that. Now, it’s much more about artistry and what you have to say.”

The need to satisfy their creative impulses dictates they play some of the new material on this tour, where two-hour shows are the norm. Critics have lauded the fearless blend of freewheeling humor, theatricality, socio-political fire and candid confessional bloodletting of recent live outings, as well as the band’s ability to breathe new life into old favorites.

Mellencamp and Wanchic would never allow themselves to sleepwalk through paint-by-number renditions of old chestnuts. They’ve stuck it out this long together, and divorce isn’t an option for one simple reason.

“It’s stubbornness together I think (laughs),” said Wanchic. “You can’t fire me. I can’t fire you. Yeah, we’re like an old married couple at this point, you know. It’s kind of like Archie Bunker and Edith (laughs) – it’s second nature. Everything is second nature, like playing live with John is second nature. I can tell when something’s about to happen.”

A cohesive group, Mellencamp’s band has spent years developing a chemistry that is unparalleled. A prodigal sister has returned, too, to bring a little fire to the proceedings.

“The newest guy in the band has been here about 18 years,” said Wanchic. “I’ve been there 43 years. The other guitarist, Andrew York, who lives in Manhattan, has been with the band for about 30 years. Lisa Germano, our original violinist, is back with us after a 20-some-year-odd hiatus, and it’s amazing having her back in the band, because all those songs … ‘Paper in Fire,’ ‘Check it Out,’ ‘Cherry Bomb’ – all those songs and similar ones, it was like something returned, you know. It was just like coming home. Having her onstage is a real gift.”

Fluent in all kinds of genres, from ‘60s soul and R&B to British rock, as well as folk and country, Mellencamp’s band communicates easily onstage.

“We’re all speaking the same language, and that’s what’s beautiful about it,” said Wanchic. “With John and I, that’s the connection we’ve had historically. I grew up in Lexington, Kentucky. He grew up in Seymour, Indiana, with the same radio station in Louisville, Kentucky, with the same DJs, so we had a very common music background.”

Wanchic was just out of college when he met Mellencamp. He wanted to learn audio engineering, but in the ‘70s, opportunities were limited.

“You couldn’t go to Berklee (College of Music),” said Wanchic. “You couldn’t go to all of the places you can go now. Indiana University, here in Bloomington, now has a massive recording arts program. Back then, you had to find someone who would allow you to intern. And so, there was one recording studio here in Bloomington – and probably all over Indiana at that point. It was owned by a guy named Jack Gilfoy, who was the drummer for the Henry Mancini Orchestra. And he was the head of the percussion department at Indiana University. And I basically went down and just badgered him enough that they gave me an internship.”

Little did he know he was about to meet the man who’d change his life.

“John came in to make his very first demos, and I was just the intern, but he had a guitar player who was marginal at best,” said Wanchic. “And the guy who was engineering the project said, ‘Let’s let Mike play guitar on these songs.’ So, after that guy would leave, I’d go in and just replace his parts and that’s where we met.”

A few years removed from those sessions, Wanchic was brought into the fold permanently. In 1979, the John Cougar LP was released, which included “I Need a Lover.” Originally on the album A Biography, the song was first a hit in Australia. Tacked onto John Cougar, it later broke into the U.S. Top 40 when the LP came out, and records that followed, such as 1980’s Nothing Matters and What If it Did and 1982’s American Fool, yielded catchy, pop-rock classics like “Ain’t Even Done with the Night,” “Jack & Diane,” “Hurts So Good” and “Hand to Hold Onto.”

Behind the scenes, tension was building. Mellencamp fiercely fought efforts to mold him into a pop star and steer him in a more commercial direction. He was battling for control, and he won.

“It’s one of those things where John could have made a lot more money quickly, but John had the foresight to say no to keep our integrity,” said Wanchic. “I’ll give you a quick example. When ‘Hurts So Good’ came out, we were the opening band for Heart on that tour. Before American Fool came out, we were the opening act. We signed a huge, long tour opening for Heart. So, we were just the kids that got the 35-minute show and while we got settled on that tour, suddenly our record went nuts – single went to No. 1, album went to No. 1 and suddenly, we were the opening act headliner. It was hard on Heart, because we were selling out the arenas, but the point being … when the first endorsement thing came by, I think it was Tobasco, they wanted to use ‘Hurt So Good.’ And it was a big check, you know? We didn’t have money at the time, and John went, ‘No.’ And we went, ‘No?’ (laughs) But, in the long haul, he was completely right. His instincts were right.”

In the process, Mellencamp’s sound started embracing Americana, gradually giving greater voice to the broken heart and soul of America’s Heartland, beginning with 1983’s rootsy rocker Uh Huh, where Mellencamp tapped into a rebellious, blue-collar sensibility that fueled fist-pumping anthems like “Pink Houses,” “Authority Song” and “Crumblin’ Down.” It was the first album he made under his real last name, and it charted at No. 9 on the Billboard 200, buoyed by three Top 20 hits. Around that time, Rolling Stone called that version of Mellencamp’s band as “one of the most powerful and versatile live bands ever assembled.” And even though some of the personnel has changed, that statement still applies for one reason.

“Work. Good old-fashioned, no bullsh*t work,” said Wanchic. “We have, over the years, been the most rehearsed, hardest-working group of people I’ve ever met in my life.”

Uh Huh kicked off a string of massive successes, just as Mellencamp became more of an activist. 1985’s Scarecrow lamented the demise of the family farm and waxed nostalgic for rural living, old-time rock ‘n roll and coming-of-age rituals on songs such as “Small Town,” “Lonely Ol’ Night,” “R.O.C.K. in the U.S.A.,” “Rumble Seat” and “Rain on the Scarecrow.” Before they went into the studio for Scarecrow, Mellencamp handed out some homework.

“Now, at one point, we even took some time off, and John kind of gave everybody an assignment and we went away as a band, and we learned like 50 songs of other artists,” recalled Wanchic. “I mean, like studying Motown – the four snares like ga-ka, ga-ka, ga-ka, that drove a Motown song. And we broke down Motown songs, and we learned what made them work and what made them click. And we did the same thing with old British music. We literally studied and then brought it back to the table and applied it to us. Same thing with Jubilee. After Jubilee, we’d made a lot of guitar-based, drum records, and John said, ‘Let’s go away and let’s pick an instrument and learn it.’ So, I went away, and I had worked on banjo, and I worked on dobro. John Cascella, our keyboard player, came clean and said he was the New Jersey state accordion champion when he was 11, much to his chagrin, because the accordion was not cool.”

Jubilee is 1987’s rousing The Lonesome Jubilee, the sublime culmination of Mellencamp’s determination to plant a flag in newly discovered alternative-country territory, a place where gospel singing, Appalachian instrumentation, snap-crackle-pop drums and acoustic and electric elements could frolic freely. Chock full of more smashes, such as “Cherry Bomb,” “Paper in Fire” and “Check it Out,” The Lonesome Jubilee was another monster release.

Suddenly, even the accordion was in fashion.

“Yeah, we made it cool,” laughed Wanchic. “And then we got Lisa in the band, and all of a sudden, we had a new thing, and that’s what Jubilee was born from. You keep working like that. You keep pushing yourself.”

With each of those records, Mellencamp had something to say.

“Absolutely. I also think it was one of those things that if you keep making the same record, it marks the end of your career,” said Wanchic. “It’s like, ‘Hey, we had a hit record. Let’s keep making it. Let’s put lipstick on a pig and keep putting it out.’ I think that’s where people sell themselves short. They don’t push. Success makes people lazy, and you think it’s going to last forever and it’s not. It’s going to last as long as your musical integrity will stay intact, you can continue to be at least progressively artistic, you know, and moving forward. You’ve got to keep moving forward. And I think that’s why we’re still making records 23 records later.”

In that spirit, Mellencamp and crew didn’t look back, releasing popular albums such as 1989’s Big Daddy, 1991’s Whenever We Wanted, 1993’s Human Wheels and 1994’s experimental Dance Naked.

“Oh my God, that was the extreme of the extreme,” said Wanchic, referring to Dance Naked. “’We’re not going to have a bass player on this record.’ ‘What? No bass player? Okay. (laughs) If you say so.’ I thought it was complete lunacy. Fortunately, we got MeShell Ndegeocello, who played bass on it. Beyond that we were just relying on a big fat kick drum. Once again, it was John having a lot of artistic bravery to say, ‘Let’s just try something different.’ And that record went platinum, mostly thanks to the No. 1 single with ‘Wild Night.’ And just growing and growing and growing … not trying to make the same record again. You do that, the clock is ticking man. Your career is marked as coming to an end.

Continuing to carve their own path, without any regard for what’s trendy or popular, Mellencamp and his crew have churned out a spate of critically acclaimed records, employing their own unique process. Nowadays, every tour is a victory lap for Mellencamp – who also paints and acts – and his co-conspirators, confirming once and for all that the hard choices they made were the right ones and that they were made for the right reasons.

“We run by one major rule: ‘Paint fast and make mistakes,’” said Wanchic. “I mean, I’m dead serious. You come up with a new idea. You throw it down. It might be a mistake, but it’s the real deal. And now, have the balls to hold onto it and not try to doll it up. I think a lot of those early records were so guitar primitive. That’s what made them so real because they were real. It was not us overthinking. If you overthink something, particularly in rock ‘n roll, you’re going lose that spirit, and we managed to catch that lightning in a bottle just because we were young, we were dumb, and we didn’t know enough to f**k it up any further. We were painting fast. We were making mistakes. We were putting ‘em down, we were keeping them, and by the grace of God, you know, people bought it and liked it. They caught onto the fact that it was straight-up honest.”